Hearing

| For most of us, our sense of hearing is something we don't think too much about, but this important ability is a big part of our neural map. Explore how you hear in this article. |

Our sense of hearing is something we often take for granted. From the moment we wake up to the moment we fall asleep, and also in fact while we’re asleep, our ears are receiving sounds, transferring them to our brains where they are processed and interpreted. More than 5% of the world's population, some 360 million people it is estimated, suffer from some degree of hearing loss, meaning that for many of us the simple pleasures of listening to music, taking part in conversation, or listening to the birds singing in the trees, is difficult.

The causes are many, and if you believe that you are experiencing hearing problems, or are at risk of doing so, it’s a good idea to speak to a specialist such as those working at Hidden Hearing to find out what is the best way forward.

Whereas smell, taste and sight use chemical reactions, hearing is different in that relies on physical movement, vibrations in the air. Here’s a rough guide to how sounds reach the brain:

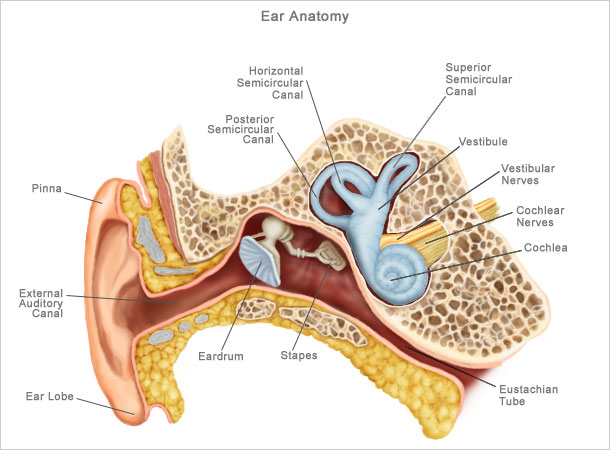

Sounds in the air are picked up by the ears, causing the eardrum to vibrate.

When the vibrations carry through to the middle ear, they encounter three bones, enigmatically named the hammer, the anvil and the stirrup. They work in conjunction with each other to amplify the sound waves.

After the middle ear, the vibrations move into the cochlea, also known as the inner ear, where they cause the fluids in there, called perilymph and endolymph, to move around.

At this stage, the brain begins to take notice. The movement of the fluid bends hair cells, which sends signals to the auditory nerve.

The brain picks up the signals from the auditory nerve and begins to interpret them.

Note: Most forms of hearing loss are caused by the hairs in the inner ear becoming damaged. This could be caused, for instance, by infection or by inserting a cotton bud into the ear, and results in signals not getting through to the brain properly.

| Related articles |

That basically covers the role of the ear. It is now up to the brain to process the sounds it is receiving which is where things start to get really interesting.

Groups of neurons are constantly decoding every sound, for example by its loudness or proximity, and arranging them to create sensations in the brain. The amazing part is that they can choose to prioritize certain sounds and vice versa, which is how we are able to conduct conversations in noisy environments or pick up the sound of our phone ringing in another room while we watch TV.

By this stage the sounds we hear have been transformed into neural processes. When they are first received they instigate a reflex action, for instance when we start to listen, or when we jump in shock at a loud noise behind us like a car beeping its horn unexpectedly.

Next, the sound is perceived, or recognized. We realize that it is just a car beeping, or that our friend has said something.

And finally, we react—we continue walking on the pavement as the car passes by, or we acknowledge what has been said with a reply.

This is a process that the brain follows when we are conscious only. When we are unconscious, usually asleep, a sound can cause a reflex—a good example is how noise outside the window may infiltrate our dreamsReflex

Perception

Reaction

A brief summary then of how our ears and brains process the sounds around us—hearing is a complicated business and vital to how we deal with the world around us. When our hearing deteriorates, whether due to age or other factors, it can be distressing, but luckily, modern technologies mean that treatment is better than ever before.

| By Debbie Fletcher | Embed |

0 comments:

Post a Comment