Neuroscience

A new study has collected data about the brain activity of poker players. The study set out to record the levels of brain activity in poker players operating at different levels of competence: the beginner, the amateur and the professional.

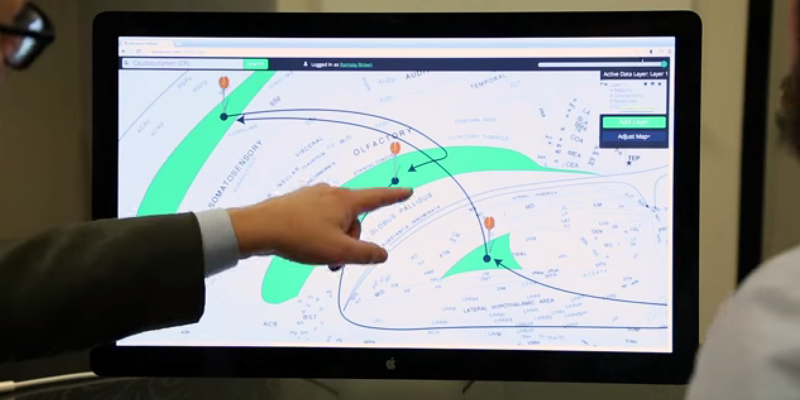

A study conducted by a London based behavioural research consultancy has collected some interesting data about the brain activity of poker players. The study set out to record the levels of brain activity in poker players operating at different levels of competence: the beginner, the amateur and the professional. Six players, two from each category, were observed playing forty minutes of Texas Hold’em poker. Half played for money, half for free. The players wore EEG headsets which recorded the location and intensity of brain activity in four areas of the brain: delta, theta, alpha and beta. This data was then converted into interactive brain maps, allowing us to observe brain activity in the players at key moments of the game.

Deal

At the start of the game the beginner shows high theta activity in the right frontal lobe, indicating high levels of emotion, in contrast, the amateur displays high beta activity in the left frontal lobe, indicating decision making driven by logic. This is the stage of the game where the amateur is most engaged and where they spend the most time processing the information. The brain map of the professional is similar but indicates a much lower level of activity. The experienced player makes a quicker decision with less mental effort.

Flop

Related articles

This is where the first three cards are placed down altogether, face up. The beginner’s brain map shows little activity. Their lack of experience renders them incapable of responding to the new data, either with emotion or logic. The amateur shows alpha activity indicating logic at work but both brain maps are in stark contrast to that of the professional where a high level of activity in both frontal lobes indicates both logical thinking and emotional instinct at work.River

This is a key phase of the game when the fifth card is placed, face up. The beginner’s brain exhibits exclusive right frontal lobe activity, indicating an entirely emotional response to the situation. The amateur brain map shows high levels of activity in both frontal lobes, with slightly more activity on the right lobe, suggesting that emotion is dominant. The effect of the final card on the professional is to stimulate a flurry of activity on the left lobe. The professional is in control of emotion and is relying on logic to make the decision.

Call

This is when a player adds to the pot, money equal to the most recent bet. The fact that this is a relatively safe play is reflected in similar brain maps for all three subjects. As we might expect, the response of the beginner is predominantly emotional whereas the brain maps for the amateur and professional show more of a spread across both frontal lobes.