Neuroscience

Researchers used a brain-to-brain interface they developed to allow pairs of participants to play a '20 question' style game by transmitting signals from one brain to another over the Internet. Their experiment is thought to be the first to demonstrate that two brains can be directly linked to allow someone to accurately guess what is on another person's mind. |

University of Washington researchers recently used a direct brain-to-brain connection to enable pairs of participants to play a question-and-answer game by transmitting signals from one brain to the other over the Internet. The experiment, published in PLOS ONE, is thought to be the first to show that two brains can be directly linked to allow one person to accurately guess what's on another person's mind.

"This is the most complex brain-to-brain experiment, I think, that's been done to date in humans," said lead author Andrea Stocco, an assistant professor of psychology and a researcher at UW's Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences.

"It uses conscious experiences through signals that are experienced visually, and it requires two people to collaborate," Stocco said.

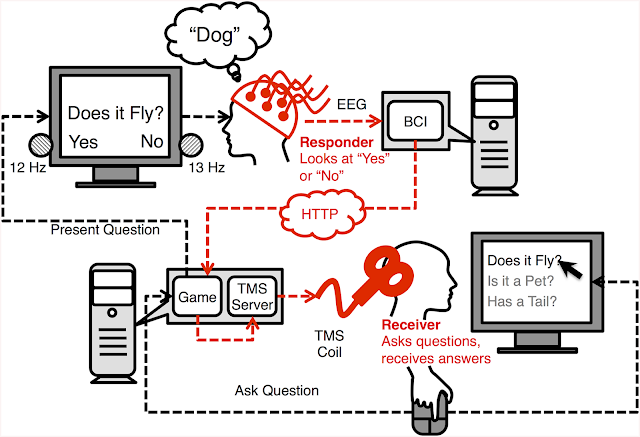

The brain-brain connection works by having the first participant, or "respondent," wear a cap connected to an electroencephalography (EEG) machine that records electrical brain activity. The respondent is shown an object (for example, a dog) on a computer screen, and the second participant, or "inquirer," sees a list of possible objects and associated questions. With the click of a mouse, the inquirer sends a question and the respondent answers "yes" or "no" by focusing on one of two flashing LED lights attached to the monitor, which flash at different frequencies.

A "no" or "yes" answer both send a signal to the inquirer via the Internet and activate a magnetic coil positioned behind the inquirer's head. But only a "yes" answer generates a response intense enough to stimulate the visual cortex and cause the inquirer to see a flash of light known as a "phosphene." The phosphene -- which might look like a blob, waves or a thin line -- is created through a brief disruption in the visual field and tells the inquirer the answer is yes. Through answers to these simple yes or no questions, the inquirer identifies the correct item.

The experiment was carried out in dark rooms in two UW labs located almost a mile apart and involved five pairs of participants, who played 20 rounds of the question-and-answer game. Each game had eight objects and three questions that would solve the game if answered correctly. The sessions were a random mixture of 10 real games and 10 control games that were structured the same way.

The researchers took steps to ensure participants couldn't use clues other than direct brain communication to complete the game. Inquirers wore earplugs so they couldn't hear the different sounds produced by the varying stimulation intensities of the "yes" and "no" responses. Since noise travels through the skull bone, the researchers also changed the stimulation intensities slightly from game to game and randomly used three different intensities each for "yes" and "no" answers to further reduce the chance that sound could provide clues.

The researchers also repositioned the coil on the inquirer's head at the start of each game, but for the control games, added a plastic spacer undetectable to the participant that weakened the magnetic field enough to prevent the generation of phosphenes. Inquirers were not told whether they had correctly identified the items, and only the researcher on the respondent end knew whether each game was real or a control round.

"We took many steps to make sure that people were not cheating," Stocco said.

Participants were able to guess the correct object in 72 percent of the real games, compared with just 18 percent of the control rounds. Incorrect guesses in the real games could be caused by several factors, the most likely being uncertainty about whether a phosphene had appeared.

"They have to interpret something they're seeing with their brains," said co-author Chantel Prat, a faculty member at the Institute for Learning & Brain Sciences and a UW associate professor of psychology. "It's not something they've ever seen before."

Errors can also result from respondents not knowing the answers to questions or focusing on both answers, or by the brain signal transmission being interrupted by hardware problems.

"This is the most complex brain-to-brain experiment, I think, that's been done to date in humans." |

| Related articles |

The study builds on the UW team's initial experiment in 2013, when it was the first to demonstrate a direct brain-to-brain connection between humans. Other scientists have connected the brains of rats and monkeys, and transmitted brain signals from a human to a rat, using electrodes inserted into animals' brains. In the 2013 experiment, the UW team used noninvasive technology to send a person's brain signals over the Internet to control the hand motions of another person.

The first experiment evolved out of research by co-author Rajesh Rao, a UW professor of computer science and engineering, on brain-computer interfaces that enable people to activate devices with their minds. In 2011, Rao began collaborating with Stocco and Prat to determine how to link two human brains together.

"Imagine having someone with ADHD and a neurotypical student," Prat said. "When the non-ADHD student is paying attention, the ADHD student's brain gets put into a state of greater attention automatically."

Many technological advancements over the past century, from the telegraph to the Internet, were created to facilitate communication between people. The UW team's work takes a different approach, using technology to strip away the need for such intermediaries.

"Evolution has spent a colossal amount of time to find ways for us and other animals to take information out of our brains and communicate it to other animals in the forms of behavior, speech and so on," Stocco said. "But it requires a translation. We can only communicate part of whatever our brain processes.

"What we are doing is kind of reversing the process a step at a time by opening up this box and taking signals from the brain and with minimal translation, putting them back in another person's brain," he said.

SOURCE University of Washington

| By 33rd Square | Embed |